Specification by example

Testing is one of the few topics developers like to avoid when possible and admittedly I am no exception here. During my career I either thought tests should be written by testing engineers or there is no sense in testing something at all. Maybe, one of the problems is that you are too close to the frontier and need to step back to see the actual benefit?

To get a broader view and understanding, I started reading about different testing ideas, strategies and methodologies. During that I learned quite a lot, like Test-driven Development can be really helpful and rewarding, but maybe this is something I can lay out in another post. Here I want to write about something that I also found interesting, namely Acceptance Testing.

Acceptance Testing &

So what do we have here? After reading the second linked Wikipedia article you should be pretty much covered, but let me still explain it in layman’s terms:

Acceptance tests are tests, that help to prove verify, that a story or more in general some feature is ready for production and this unit of work is done. So far, so good.

Now the tricky question: When are these tests defined and by whom actually?

Both when and by whom are interesting, since it is a bit different than my past self would have expected. I wrote above, that I expected test engineers to write all kind of tests and this isn’t so far from the truth. Another expectation was, that these test engineers either write tests in parallel, while the developer writes the code or afterwards, once development is done.

Knowledge Sharing &

This flow has some inherent problems about knowledge sharing: Developers can only catch problems they are aware of, Rumsfeld got the gist of it nicely with his phrase about unknown unknowns. And testers have their own share of knowledge about this specific type of product or even better some testing heuristics.

| There is a nice test heuristics cheat sheet though. |

Like so often in our business, communication is key and some of the problems can be easily avoided, when developer and tester start talking to each other before any actual work is done.

Three Amigos &

Three Amigos or Specification Workshop is a way to get this started: When a new story has to be written, the story’s stakeholder, a developer who will most likely be tasked with it and a tester have a short session about what has to be done. During this session, they share their knowledge, talk about edge cases and define test cases how this story can be verified and accepted.

The format of the output is completely open, ranging from simple lines written down on the story card or a rough table with values of edge cases, that have to be considered. The key here is the exchange of knowledge, which directly improves the understanding of the story of the participants and also might lead to interesting questions and problems.

Let us talk about some of the existing tools to support this now.

Tools &

Cucumber &

If you fire up Google and search for tool for automated acceptance testing, one of the first few

matches is probably Cucumber, obviously depending on your personal filter bubble.

It uses the given-when-then format (originally invented by Dan North) to write

structured test cases and to evolve a domain-specific language) for use cases in a language

called Gherkin.

The resemblance between given-when-then and the format coined by Connextra is no accident: The idea here is to directly be able to translate one to the other.

Getting started with Gherkin is pretty easy and self-explanatory. I don’t want to go much in gory detail, so it probably suffices to say there is the set of three commands and some conjunctions to formulate the use case, similar to the english language (or some other; there is support for a few) and example values can be loaded from tables:

Feature: Create a todo

Create various todo entries to test the endpoint.

Scenario Outline: Create a todo with title and description and check the id.

Given I create a todo with the title "<title>"

And the description "<description>"

Then its id should be <id>

Examples:

| title | description | id |

| title1 | description1 | 1 |

| title2 | description2 | 2 |As you can see, the format of features is pretty open and the only limit is probably the creativity of the writer. With this at hands it is easy to invent some kind of language for the business cases and doesn’t matter if it’s targeted to finance, logistics or insurance.

Once the feature is ready, someone needs to write the test fixture or steps in the lingo of Cucumber. Here is a small excerpt from my showcase:

public class TodoSteps {

@Given("I create a todo with the title {string}")

public void given_set_title(String title) {

this.todoBase.setTitle(title);

}

@And("the description {string}")

public void and_set_description(String description) {

this.todoBase.setDescription(description);

}

}The Java bindings provide us with lots of convenient annotations to handle the string matching and we can assemble the test piecemeal.

So let us check the output of the Cucumber test runner:

Scenario Outline: Create a todo with title and description and check the id. # src/test/resources/features/todo.feature:11

Given I create a todo with the title "title1" # dev.unexist.showcase.todo.domain.todo.TodoSteps.given_set_title(java.lang.String)

And the description "description1" # dev.unexist.showcase.todo.domain.todo.TodoSteps.and_set_description(java.lang.String)

Then its id should be 1 # dev.unexist.showcase.todo.domain.todo.TodoSteps.then_get_id(int)So let us take a step back and talk about what we have archived so far:

-

We’ve created some kind of language with a modest chance, that it is understandable by other than technical folks, although they will probably never check out the source code to read it and have to rely on reports.

-

We can split the task of writing the fixture and the steps, but introduce problems how to combine them again and how to make the results visible.

-

And we’ve introduced tables for values, which makes the testing pretty easy and understandable.

Let us check how FitNesse tries to solve these problems.

FitNesse &

Fitnesse is another testing framework, which also uses the table approach, but provides access to the test cases, definitions and results in a unique way: It comes bundled with a standalone wiki engine and can be accessed with any browser:

Before you ask, yes you can also run it headless in case you want to integrate it into a CI pipeline. We all know that you want to do that, right?

$ java -jar lib/fitnesse.jar -c "FrontPage?suite&suiteFilter=MustBeGreen&format=text"The wiki itself consists of different types of pages: - Static, normal pages like the ones you know from Wikipedia. - Suites, collections of different test pages, which can be executed. - Tests, actual test cases, which also can be executed.

Depending on the testing engine, a suite requires some additional setup. In my examples I’ve used the SLiM engine and this looks like this:

!1 Test Suite for Slim based REST calls

This suite just consists of a single test of the endpoint.

----

!contents -R2 -g -p -f -h

!*< SLiM relevant stuff

!define TEST_SYSTEM {slim}

!path /Users/unexist/Projects/showcase-testing-quarkus/todo-service-fitnesse/target/classes/

!path /Users/unexist/Projects/showcase-testing-quarkus/todo-service-fitnesse/target/test-classes/

!path ${java.class.path}

*!

----

The markup is a bit different than you are probably used to, so here is quick heads up:

Commands usually start with an exclamation point (like `!path`) and the output of anything

enclosed in asterisks is silently consumed.

Let us talk about an actual test page:

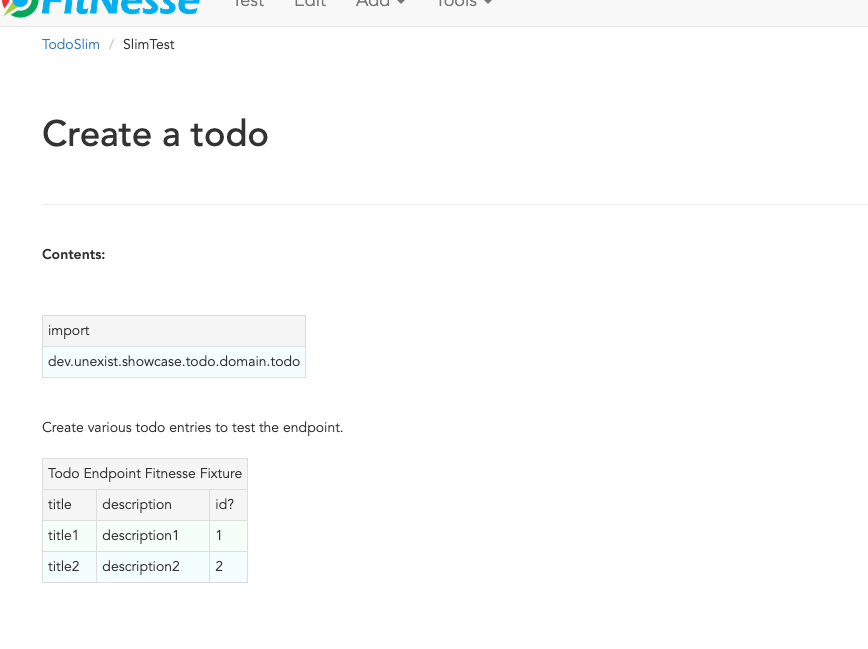

====== **Wiki: Test SlimTest**:

```asc

!1 Create a todo

----

!contents -R2 -g -p -f -h

|import|

|dev.unexist.showcase.todo.domain.todo|

Create various todo entries to test the endpoint.

!|Todo Endpoint Fitnesse Fixture |

| title | description | id? |

| title1 | description1 | 1 |

| title2 | description2 | 2 |The interesting points here are the two tables: The first one specifies the path to the fixture that should be imported for this test and the second one the actual values. Although a bad example, I used the same table structure from the Cucumber example just to make my point later in this blog post.

And here is another excerpt from the fixture:

public class TodoEndpointFitnesseFixture {

private TodoBase todoBase;

private RequestSpecification requestSpec;

public void setTitle(String title) {

this.todoBase.setTitle(title);

}

public int id() {

String location = given(this.requestSpec)

.when()

.body(this.todoBase)

.post("/todo")

.then()

.statusCode(201)

.and()

.extract().header("location");

return Integer.parseInt(location.substring(location.lastIndexOf("/") + 1));

}

}FitNesse automatically uses the column names of the table as the accessors of the fixtures,

so the column title directly relates to the setter setTitle and id? to the getter id.

I am not entirely sure why, but at least we got rid of half of the bean spec.

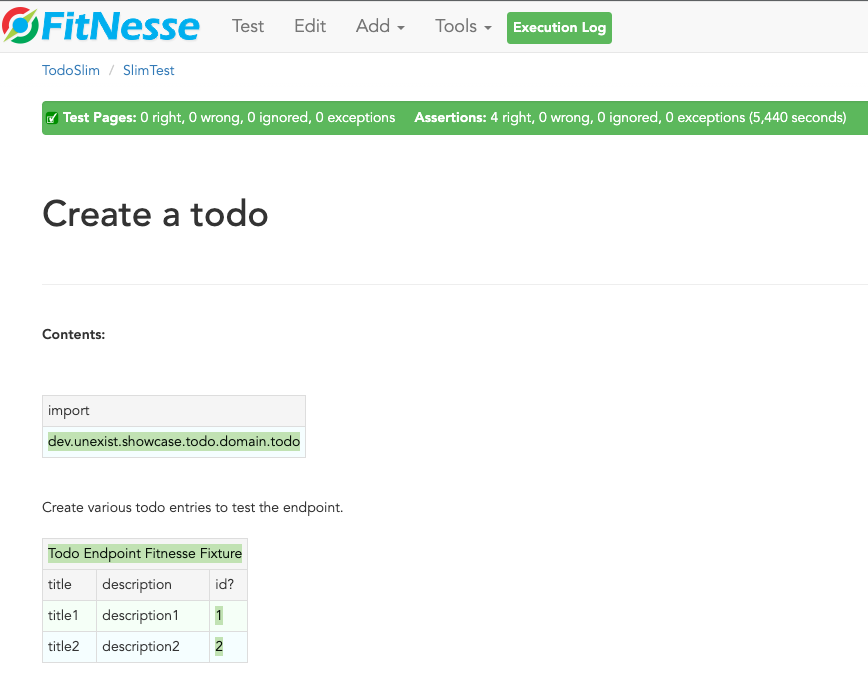

Back to your browser: When you click on the test button at the top, FitNesse fires up and runs the tests on the selected page - or the entire suite and updates the colors according to the results:

Let us talk about the problems I’ve mentioned before:

-

FitNesse solves the problem how non-tech-savy folk can write and run tests and also allows a quick verification just with the use of a browser, when properly set up.

-

It kind of lacks the benefits of the DSL, but from my experience it all boils down to lots of tables anyway. (FitNesse is extendable and there are some outdated projects like fitnesse-cucumber-testing-system which I am trying to fix here though)

-

The idea with the table is pretty similar to the one of Cucumber.

Let us talk about number three.

Concordion &

Concordion is the latest addition in my showcase and also in the overall list of frameworks that I gave a try. It is a bit similar to the idea of Cucumber, with the exception that instead of Gherkin it instruments markdown to bring flexibility to the specification itself.

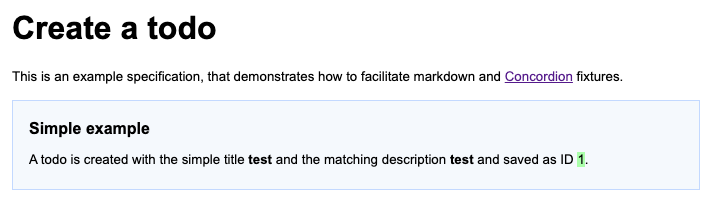

This is easier shown than it is to explain:

# Create a todo

This is an example specification, that demonstrates how to facilitate markdown

and [Concordion](https://concordion.org) fixtures.

=== [Simple example](- "simple_example")

A todo is [created](- "#result = create(#title, #description)") with the simple

title **[test](- "#title")** and the matching description

**[test](- "#description")** and [saved](- "#result = save(#result)") as ID

[1](- "?=#result.getId").Besides the usual markdown formatting, the interesting parts are the links:

-

If you attach something like

#titleto a word, Concordion puts the word into the named variabletitle. -

If you use an equal sign like

#result = #title, you create an assignment. -

If you write something like

createyou call a function of the underlying fixture. -

If you start with a question mark like

?=#resultyou make an assertion of equality.

In the above example we create a Todo from a title and a description, this is a pretty easy case and visible in the following excerpt from my showcase

@RunWith(ConcordionRunner.class)

public class TodoConcordionFixture {

public TodoBase create(final String title, final String description) {

TodoBase base = new Todo();

base.setTitle(title);

base.setDescription(description);

return base;

}

}When the test runner runs this test it creates following report:

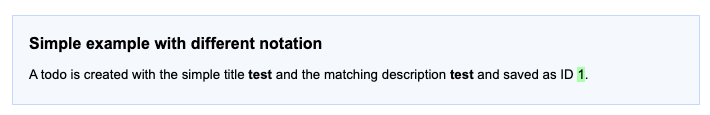

Since adding all the link instrumentation directly into the text makes its source kind of difficult to read and follow, therefore there is a slighty extended way of creating them:

=== [Simple example with different notation](- "simple_example_modified")

A todo is {createdCmd}[created] with the simple title **[test](- "#title")** and

the matching description **[test](- "#description")** and {savedCmd}[saved]

as ID [1](- "?=#result.getId").

[createdCmd]: - "#result = create(#title, #description)"

[savedCmd]: - "#result = save(#result)"This example utilizes another way of defining links inside of markdown, which is quite handy for me because I usually do it that way in my blog as well. Once the runner writes the report it can be opened in your browser:

All the other examples use a table, so here is a small example with a table as well:

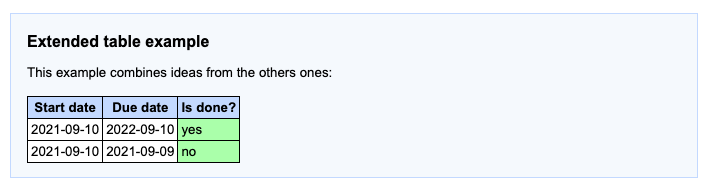

=== [Extended table example](- "extended_table")

This example combines ideas from the others ones:

| {}[createWithDate]{start}[Start date] | {due}[Due date] | {done}[Is done?] |

| ------------------------------------- | --------------- | ---------------- |

| 2021-09-10 | 2022-09-10 | undone |

| 2021-09-10 | 2021-09-09 | done |

[createWithDate]: - "#result = createWithDate(#start,#due)"

[start]: - "#start"

[due]: - "#due"

[done]: - "?=isDone(#result)"To ease the writing of the tests, we just have to instrument the names of the columns, but it is

quite possible to do this in every row.

The initial createWithDate is a special case and runs before each row.

If we task our test runner again to get the report we end up with this:

Time for talk about the usual points:

-

The generation of the reports is a nice addition to make it easier to read the results of a test and the possibilities of markdown even allow the linking of different files.

-

The approach of Concordion is a bit different, instead of relying on a DSL like Cucumber or on tables only like FitNesse, it allows to easily use natural language and enhances it. This moves some of the complexity of the specification to the writer and probably limits who can do that at all.

-

And we have another pretty similar approach here.

Conclusion time!

Conclusion &

The idea of specifications is to have some kind of living document, that can be used to transport the intent of a feature and also show noteworthy edge cases of the implementation. They will outlast tickets and should be the first address to go to, to understand how something works.

All three frameworks have some pros like focus on ease of writing or how to bring a specification closer to a non-techy audience and cons like putting complexity to multiple places.

For whatever framework you choose, the real gain lies in communication: You are making a huge step forward, if you sit together, talk about story cards and actually share your knowledge and come to a shared understanding.

I must admit I am personally totally intrigued by Concordion, I really like the flexibility of the specifications and the nice reports, but unlike Cucumber I’ve never seen it in a real project. And since I don’t want to favor tech because it is tech, I promise will carefully consider the requirements and trade-offs and try to make an educated guess what to pick.

My showcase can be found here: